[print-me]

A gateway to nurturing small and sick newborns

India accounts for almost one quarter of the global burden of neonatal deaths; its preterm birth rate is close to 13%; and 28% of newborns have a low birthweight. The Government is committed to improving newborn health and has made it a priority of the National Health Mission and the Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health strategic framework (RMNCH-A). Challenges lie not only in saving lives but also in improving the quality of care and developmental outcomes among high-risk neonates: care of small and sick newborns is an important area which needs more attention.

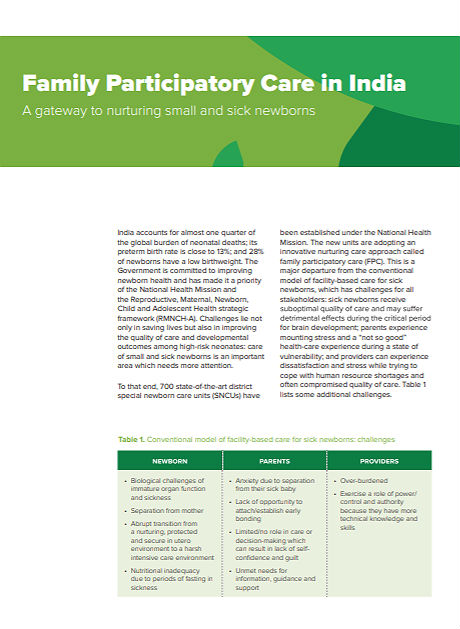

To that end, 700 state-of-the-art district special newborn care units (SNCUs) have been established under the National Health Mission. The new units are adopting an innovative nurturing care approach called family participatory care (FPC). This is a major departure from the conventional model of facility-based care for sick newborns, which has challenges for all stakeholders: sick newborns receive suboptimal quality of care and may suffer detrimental effects during the critical period for brain development; parents experience mounting stress and a “not so good” healthcare experience during a state of vulnerability; and providers can experience dissatisfaction and stress while trying to cope with human resource shortages and often compromised quality of care. Table 1 lists some additional challenges.

Table 1: Conventional model of facility-based care for sick newborns: challenges

NEWBORNS PARENTS PROVIDERS

Nutritional inadequacy due to periods of fasting in sickness Unmet needs for information, guidance or support

Abrupt transition from a nurturing, protected and secure in utero environment to a harsh intensive-care environment Limited or no role in care or decision-making which can result in lack of self-confidence and guilt

Separation from mother Lack of opportunity to attach/establish early bonding Exercise a role of power/control or authority because they have more technical knowledge and skills

Biological challenges of immature organ function and sickness Anxiety due to separation from their sick baby Over-burdened

Family participatory care nurtures sick newborns

FPC nurtures the family’s vital role in caring for their young infant throughout the period of hospitalization (see Box 1). This approach was first implemented in 2008 in a busy tertiary level neonatal unit in New Delhi as a desperate measure to overcome severe health workforce constraints. Attention was drawn to family members who spent anxious days outside the unit waiting until the baby was discharged. It was decided to teach them to provide essential care to their own baby in the nursery.

A randomized controlled trial involving caregivers demonstrated the benefits of family-centred care: i.e. improved breastfeeding before discharge, and no increase in nosocomial infections or adverse events.1 Based on this experience, four skills and knowledge sessions defining the scope of mother/caregiver involvement were developed. These are:

1) hand-washing skills; importance of infection prevention; protocol for entry to nursery;

2) developmentally supportive care (cleaning, sponging, positioning, nesting, handling and interacting with the baby; breastfeeding techniques, expression of breast milk and assisted feeding);2

3) kangaroo mother care; and 4) preparation for discharge and care at home.

In 2014, based on this evidence, the Government of India approved field testing of this model as a collaboration between Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital in New Delhi and the Norway–India Partnership Initiative in five district SNCUs in four states. After demonstrating its feasibility, benefits and acceptability, 85 districts adopted the strategy.

| Box 1. Nurturing care for the sick newborn The idea of FPC is simple – to involve parents in the care of their sick newborn from hospital admission until discharge and to respond to their needs and rights as parents. FPC is a humane way to restore the baby to the family’s embrace, protecting the baby from the negative effects of separation and promoting behaviour conductive to optimal brain development. Parents are empowered and encouraged to participate in responsive caregiving to their sick/small neonate, providing love, affection and soothing touches while caressing and cooing to their baby. These actions are crucial in this critical early period of development, establishing a sound attachment with the baby and laying foundations for lifelong bonding with both mother and father, as well as improving mutual relations within the family. The FPC approach allows both mother and father to enjoy continuous access to babies in partnership with the nursing staff. It creates an environment that is both developmentally supportive for the sick baby and culturally sensitive and responsive to the family’s need for emotional support and information. This also facilitates lactation, empowers families and helps them cope with the stresses of parenting. It allays their anxiety and builds a relationship of trust with the medical staff, thanks to transparency of care. Overall, it provides parents with a positive health-care experience. FPC also enables at-risk neonates to transition smoothly from hospital to home – ensuring a continuum of care that increases their chance of surviving and thriving after discharge. |

Implementation challenges

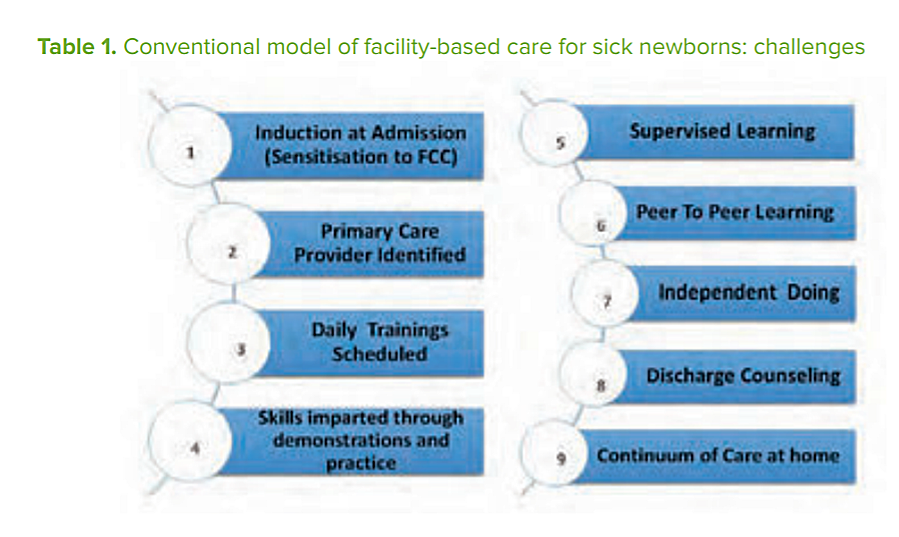

To implement FPC, three important domains need to be addressed: the infrastructure/ design of the unit (physical comfort to families); staff attitudes (empathy and support towards families); and practices that empower family caregiving. Figure 1 sets out the process of operationalizing FPC at a neonatal unit, from admission to discharge and care at home.

The process appears simple but is deceptively challenging to implement, primarily because it is not easy to persuade providers to accept parent-attendants as partners in care. Underlying reasons may include feelings of diminished authority while being watched by an informed parent, and being held to account to deliver a high standard of care.

Providers are also expected to train parents, address their needs for information, guidance and support, monitor them and provide supportive supervision.

Other important elements include effective and respectful communication and carefully planned and executed joint decision-making. Importantly, it must be remembered that the primary responsibility for medical care rests with the provider at all times, and cannot be transferred to the parents. Despite these challenges, once the providers are on board the entire culture of a neonatal intensive care unit changes, quality of care improves and newborns survival rates increase.

Evidence of impact

In externally evaluated qualitative research at Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital in 2016, acceptability of and positive attitudes towards FPC were documented among both health-care providers and families. Additionally, parents continued to use their caregiving skills at home.

The Norway–India Partnership Initiative has revealed the following:

- implementation started in 85 neonatal units in three states with state funding;

- 13,213 (75%) mother and family members received capacity-building FPC sessions;

- 5,548 (86%) newborns below 2,000 grams were provided with kangaroo mother care until discharge;

- initial assessment of mother- y dy s showed rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 86%, and continuation of kangaroo mother care at home at 75%; and

- post-discharge mortality reduced from 7% to 2.7% in the implementing districts.

Looking forward

Looking forward

Now established as a national programme, FPC led to a paradigm shift in the treatment of sick newborns, covering all components of nurturing care. FPC primarily benefits the poorest and most vulnerable, because they use public sector facilities where staffing ratios are low and quality of care is often poor. It may also improve gender equality by involving both mothers and fathers equally in caring for their newborn children. With the recent release of National Operational Guidelines on Family Participatory Care in 2017 by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, states across India have planned and budgeted for scaling up of FPC. In this way FPC will link ECD from the health facility to the community by empowering parents of babies who had the toughest start in life because of being born small or unwell.

Endnotes:

1 Verma A, Maria A, Pandey RM, et al. Family-centered care to complement care of sick newborns: a randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatr 2017. 54:455–459. http://indianpediatrics.net/june2017/455.pdf (accessed 17 May 2018).

2 For example see: Session 2 – Developmental supportive care https://youtu.be/ALoGXC6-RQk (accessed 17 May 2018).

Acknowledgements: This profile was developed in support of Nurturing Care for Early Childhood Development. A framework for helping children to survive and thrive to transform health and human potential.

Writers: India: Mrs Preeti Sudan, Mr Manoj Jhalani and team, Mrs Vandana Gurnani, Dr Ajay Khera, DR PK Prabhakar, Ministry of Health, Government of India; Prof. Arti Maria and team of Dr RML Hospital, New Delhi, India; Dr Harish Kumar, Dr Ashfaq, Dr Dipti Jhpiego NIPI Team; State Health Societies.

Acknowledging all newborns and their families.

Contributors to development and review: Matthew Frey, Bettina Schwethelm. Design: PATH. For more information, please see www.nurturing-care.org or contact NurturingCare@who.int